Yaxchilán

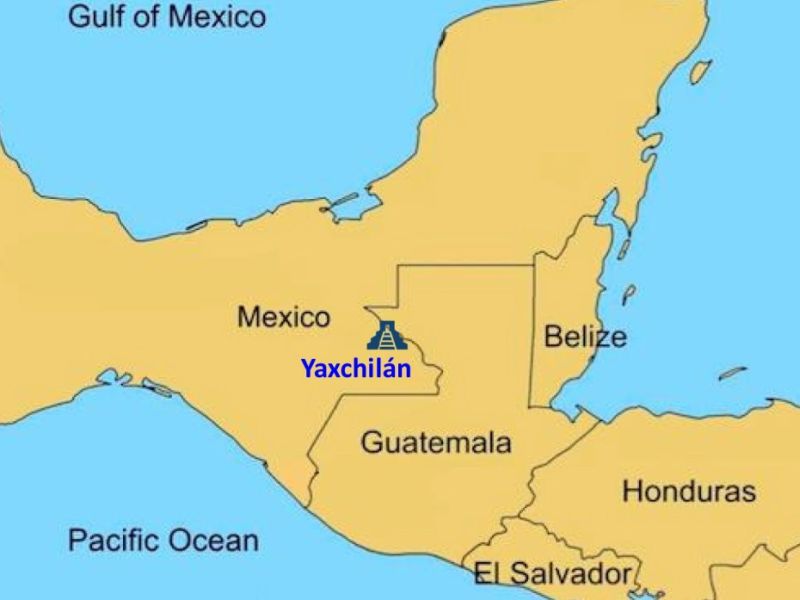

Yaxchilán is located on the Usumacinta River in what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas. The city is located in a river bend on the Rio Usumacinta not far from the border between Mexico and Guatemala, and is thus bordered on three sides by a river.

For a long time, no road led closer than 100 miles to the city. The only way to get to Yaxchilán was to travel hundreds of miles by river or by air. It was not until Mexico expanded the highway along the border with Guatemala in the early 1990s that the city became accessible to tourists. Now it is at least possible to reach the city during a one-hour boat trip on the Usumacinta.

Unfortunately, the buildings of Yaxchilán have been damaged and eroded by floods over the centuries. Further from the river, however, there are several small hills on the west and east sides on which platforms and terraces were built. Much of the preserved architecture is in the Petén style, as found at Tikal, and contact between the two sites was established through royal marriages. In addition, narrow multiple entrances and ornate roof ridges recall Palenque.

The historical name of the city was probably Pa' Chan. The present name Yaxchilán ("Green Stones") was given to the Maya city at the end of the 19th century by the German-Austrian archaeologist Teobert Maler.

In the course of deciphering Maya hieroglyphs, the original name of the site was sought and a glyph was identified as the emblem of the city, initially read as Siyaj Chan ("born in heaven" or "born heaven"). However, the glyph could also be read as Pa' Chan [paʔ tʃan] ("Divided Heaven").

Yaxchilán is still sometimes visited today by traditional Lacandon people to worship the ancient Mayan gods.

Yaxchilán was an important city during the Classic period and the dominant power in the Usumacinta region. The city ruled over other smaller cities such as Bonampak and was allied for a long time with Piedras Negras and at least briefly with Tikal. Yat-Balam, founder of a long-ruling dynasty, ascended the throne on August 2, 320, when Yaxchilán was still an insignificant city. Under the rule of his successors, the city-state grew to become the capital of the region. It waged war with the rival city of Palenque in 654. The dynasty lasted until the early 9th century. Yaxchilán had its greatest power during the long reign of King Shield-Jaguar II, who died in 742 at over 90 years of age.

One of the most impressive Petén-style buildings is the symmetrical Structure 33, built around 750 A.D. and accessed by a double platform with stairs whose crest is supported by interior buttresses. The structure was built in honor of the Yaxchilan ruler Bird-Jaguar (ruled 752-768 AD), whose likeness can be seen in stucco decorations in the center of the building's roof crest. In front of the building is a carved stalactite representing a sacred cave. Bird-Jaguar continued to expand Yaxchilán, constructing no less than eleven other buildings and 33 monuments.

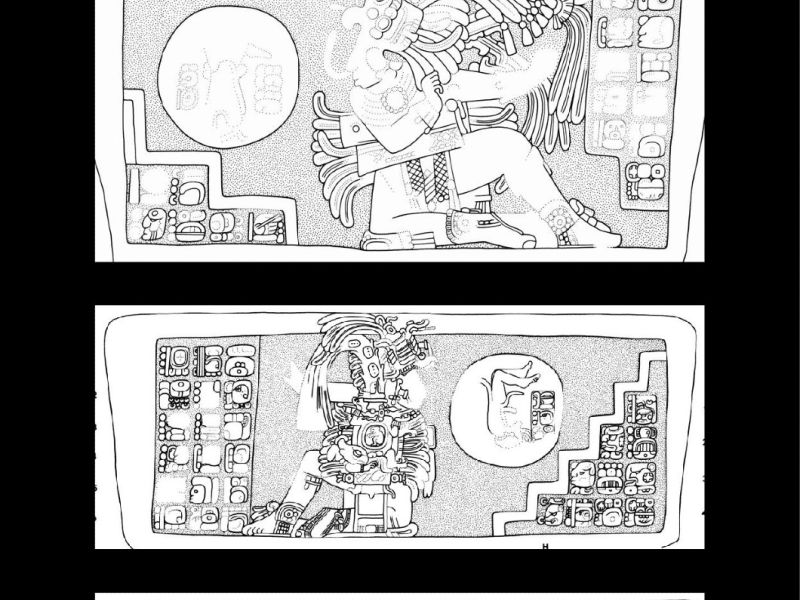

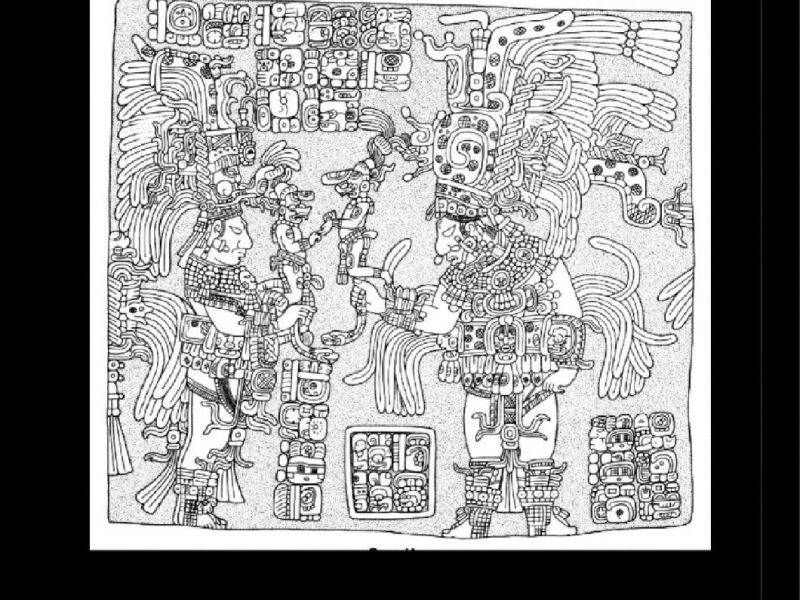

The images on the lintels of Building 33 are accompanied by glyphic texts describing each action. In the case of the lintel images of Structure 33, all of the actions are ritual dances.

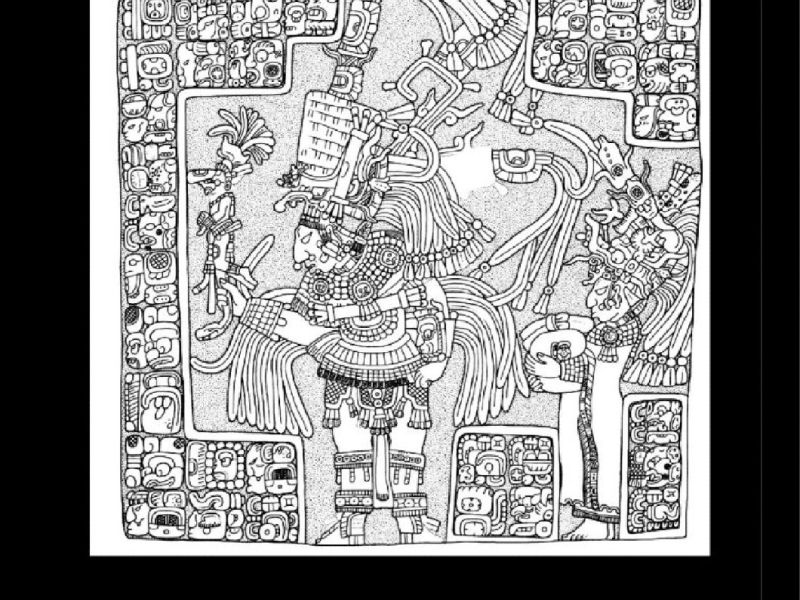

Lintels 1 and 3 are shown in the photogallery.

Lintel 1: The intel shows Bird Jaguar IV dancing with one of his wives or consorts, Lady Great Skull. The king holds a K'awiil scepter in his hand, while Lady Great Skull carries a large jade bundle. The text suggests that this event took place in front of a large crowd.

Lintel 3: The lintel shows Bird Jaguar IV dancing with a secondary ruler (sajal), with K'in Mo' Ajaw. Both the king and his sajal handle K'awiil scepters to commemorate the first hotun of the seventeenth katun. Lintel 3 is dated 9.16.5.0.0 1 Ajaw 8 Sotz in the Longcount, or April 8, 756 AD.

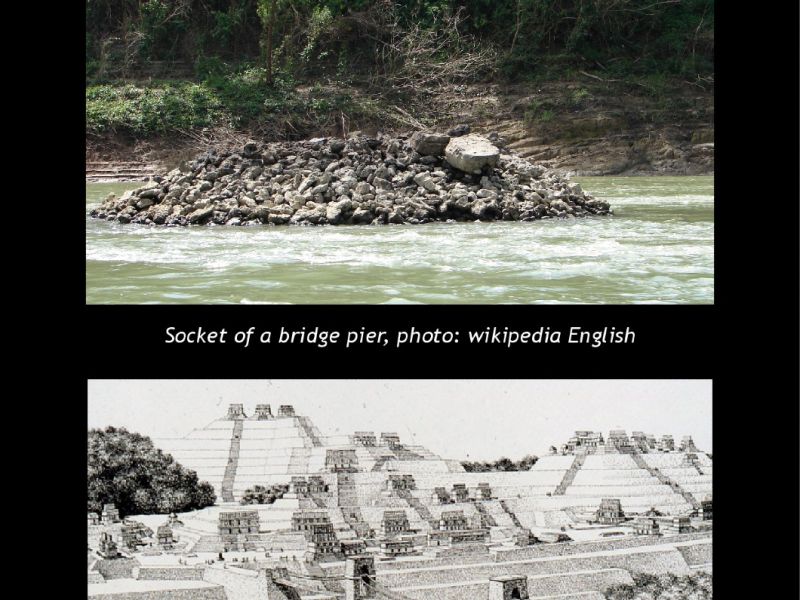

The bridge of Yaxchilán

It is believed that the Maya solved this urban traffic problem by building a 100-meter suspension bridge over the wild river in the late 7th century. The bridge, with three spans, extended from a platform on the great plaza of Yaxchilan across the river to the north bank. The middle span of 63 meters would have been the longest in the world until the construction of the Italian Trezzo sull'Adda bridge in 1377. It would have required two piers in the river; a computer model illustrates this theory.

National Geographic magazine, 1995